Publications

The Case for Haitian Reparations

Haitians are asking the French government to return some of what was stolen.

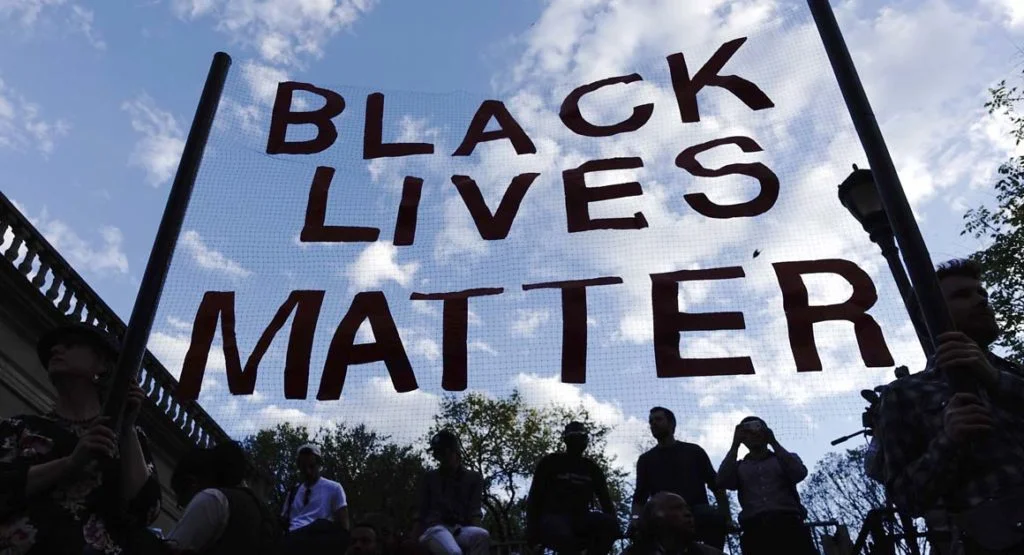

New Age Activism: Maria W. Stewart and Black Lives Matter

The 1830s was the high-tide of Jacksonianism, an era many historians consider the nadir of early American history.

The 1830s was the high-tide of Jacksonianism, an era many historians consider the nadir of early American history.

Centrist Liberalism and the Myths of the American Past

Whether the Obamas, the Clintons, or the Bushes, the scions of centrist liberalism have not provided a genuine repudiation of Trumpism. Even as hundreds of thousands of immigrants face eminent deportation schemes; even as the pharmaceutical industrial complex profits from the addiction of the white working classes; even as American Indians fight to repel centuries of resource exploitation, former president Obama retains his “Audacity of Hope,” telling the poor, the working classes, and the disaffected that if they had to choose a time in which to be born, “Now is the greatest time to be alive.”

Whether the Obamas, the Clintons, or the Bushes, the scions of centrist liberalism have not provided a genuine repudiation of Trumpism. Even as hundreds of thousands of immigrants face eminent deportation schemes; even as the pharmaceutical industrial complex profits from the addiction of the white working classes; even as American Indians fight to repel centuries of resource exploitation, former president Obama retains his “Audacity of Hope,” telling the poor, the working classes, and the disaffected that if they had to choose a time in which to be born, “Now is the greatest time to be alive.”

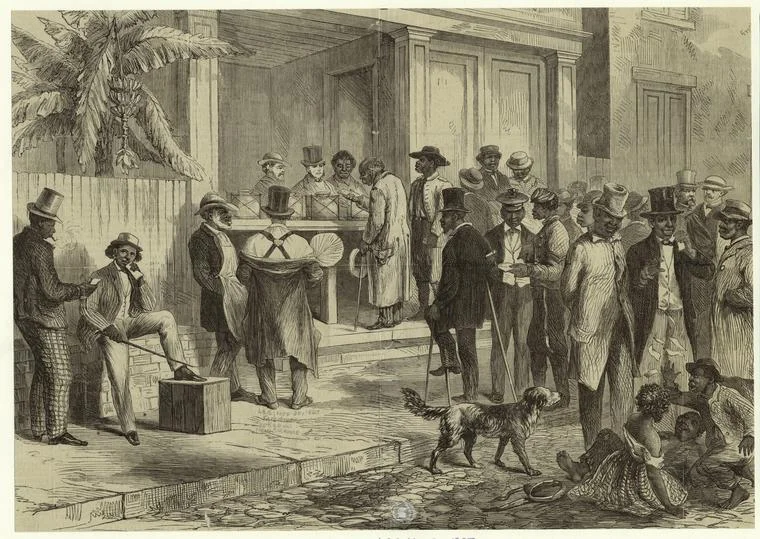

The Gift of Black Folk and the Emancipation of American History

“Our song, our toil, our cheer, and warming have been given to this nation in blood-brotherhood. Are not these gifts worth the giving? Is not this work and striving? Would America have been America without her Negro people?” — W.E.B. Du Bois, The Souls of Black Folk

“Our song, our toil, our cheer, and warming have been given to this nation in blood-brotherhood. Are not these gifts worth the giving? Is not this work and striving? Would America have been America without her Negro people?” — W.E.B. Du Bois, The Souls of Black Folk

Historical Amnesia and the Burden of the Euro-American Past in the Age of Trump

President Trump’s administration has unleashed a powerful nativist movement anchored on racist and xenophobic sentiments. Yet, the “Muslim Ban” notwithstanding, conventional wisdom, especially in liberal circles, would still have us believe the gospel of American exceptionalism as a home for refugees, the tired masses, and the poor. This narrative of America’s enlightened benevolence posits Trump as an aberration of American humanitarian norms and values. As a result, it disavows the past to explain the rise of Donald Trump as an enigma.

President Trump’s administration has unleashed a powerful nativist movement anchored on racist and xenophobic sentiments. Yet, the “Muslim Ban” notwithstanding, conventional wisdom, especially in liberal circles, would still have us believe the gospel of American exceptionalism as a home for refugees, the tired masses, and the poor. This narrative of America’s enlightened benevolence posits Trump as an aberration of American humanitarian norms and values. As a result, it disavows the past to explain the rise of Donald Trump as an enigma.

The Racial Fault Lines of American History in Trump’s America

The story of American freedom and racism is, in this sense, a twinned legacy of a dual consciousness: on one side is the story of Euro-America, of building the proverbial city on a hill, one that cast its light throughout the land of dispossessed Native Americans and towards a manifested destiny, looking towards the darker people of the Pacific. On the other side are African-Americans, who were often the casualty of Manifest Destiny, not its beneficiaries.

Consider This: Language and the Problem of Translation

Just read this beautiful New Yorker piece about language. As someone who is multilingual, it helped me reflect a bit on the constant negotiation between three languages.

Find the piece here:

http://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2016/08/08/lauren-collins-learns-to-love-in-french

I recently read this New Yorker piece that helped me reflect on what it means to be multilingual as a writer and negotiating between three languages. For readers interested, the piece can be found here: http://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2016/08/08/lauren-collins-learns-to-love-in-french

An Excerpt:

"Thanks to the Normans, who invaded England in the eleventh century, somewhere between a quarter and half of the basic English vocabulary comes from French. An English speaker who has never set foot in a bistro already knows an estimated fifteen thousand words of French."

My Reflection: The excerpt above perhaps explains why I found English exciting and fun. It also puts into perspective how easy it was to learn the language as quickly as I did as a child. Nevertheless, added to that is the difficulties that I experienced over the years as a writer who navigates the contours of thinking and reading in three languages; all this while writing in only one of them in the main. My writing occasionally suffers from conflating the Germanic and Frankish roots of English. I have often substituted longer words (French) for simpler, shorter ones (primarily Germanic). This results in an abundance of long words scattered on the page. Strunk & White, that precise little book of writing instructions, advises writers to avoid this verbosity. Although reputedly "fancy" and sophisticated, my penchant for using French has never been about supposed pretension. Instead, it has much to do with my Francophone background as Haitian. The more I write, the more I naturally gravitate towards the French inflected words in the English language. As my wonderful public school teachers noticed, this was true about my writing since junior high school. French is simply more familiar and aesthetically pleasing to my ears. This familiarity poses a challenge: how to delicately balance the fact that every French word I come across, though logical in my head, does not necessarily express what I hope to convey to readers. In other words, what sounds, looks and read well to my senses, does not always translate to effective communication on the page.

To complicate matters, I sometimes feel at a loss for words when sorting between three languages in my head. This is largely because I have to distinguish between similar and dissimilar words that may or may not mean the same thing depending on appropriate context and usage. English, after all, is both a powerfully invasive, albeit also evasive, language. What's more, this triangulation irritates when I find that I cannot converse in either Haitian Kreyol or French with as much ease as I can in English. To a degree, this makes sense. According to linguists, Haitian Kreyol's super-stratum is French. Its other variants are the West African languages, which constitute the substratum of the language. The French part makes up 90% of Haitian Kreyol's vocabulary. This fact, however, does not mean a direct connection exists in their respective grammars. The semantic evolution between them shows the vocabulary in both languages as etymologically rooted in French. Regardless of this shared parentage, French and Kreyol do have significant differences in how their meanings are culturally deployed by Haitian and French societies. That is because Haitian Kreyol's infused French retains its vocabulary from the 17th and 18th centuries’ French once spoken by white colonists and the Africans they enslaved. Today’s mainland French is not so frozen in time and place. This is true in spite of the regulations of l’Academie Francaise.

Depending on how you look at it, my multilingualism is either a gift or a curse. But I’d rather believe it constitutes a beautiful struggle. I have the privilege to wrestle between 3 languages with shared tongues, bonded by histories, both the beautiful and the ugly, but diverging in evolutionary terms. If there is a paradox, or dialectic, in this struggle, it’s that I’m also bridging the tensions they carry with respect to each other. As Walt Whitman would say, I contain multitudes. In this case, it’s a multitudinous chaos of cultures forced into mutually unintelligible translations. After 18 years, English is supplanting Haitian-Kreyol as my first language. I perceive this to be true because, in the past five years, I’ve dreamt more in the former than in the latter. I have become more lackadaisical with my Kreyol or French, speaking English even with siblings where I could settle for French or Kreyol instead. To my defense, this has largely to do with the fact that English is both more convenient and less arduous when recalling words. I estimate that I spend some 75% of my life (especially since college) conversing in English. Meanwhile I’m still more inclined to count in French, a most basic mental activity. While mutually incomprehensible, it is to Kreyol that I look for making sense of the unintelligible French.

Watch my 2015 Gilder Lehrman Fellow Interview

Founded in 1994, the Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History is a nonprofit organization supporting the study and love of American history through a wide range of programs and resources for students, teachers, scholars, and history enthusiasts throughout the nation. The Institute creates and works closely with history-focused schools; organizes summer seminars and development programs for teachers; produces print and digital publications and traveling exhibitions; hosts lectures by eminent historians; administers a History Teacher of the Year Award in every state and U.S. territory; and offers national book prizes and fellowships for scholars to work in the Gilder Lehrman Collection as well as other renowned archives.

External Links

100 Years of Perpetual Occupation: Woodrow Wilson’s Legacy in Haiti

Admirers of Woodrow Wilson overlook his crimes against the Haitian people a century ago.

Admirers of Woodrow Wilson overlook his crimes against the Haitian people a century ago.

For the reverberations of Wilsonian racism, look no further than the island nation of Haiti. The two countries share a revolutionary heritage that began with independence—the U.S. in 1776, then Haiti in 1804—against European colonialism. However, that shared legacy was short-lived as racism increasingly defined U.S. policies toward the Haitian republic.